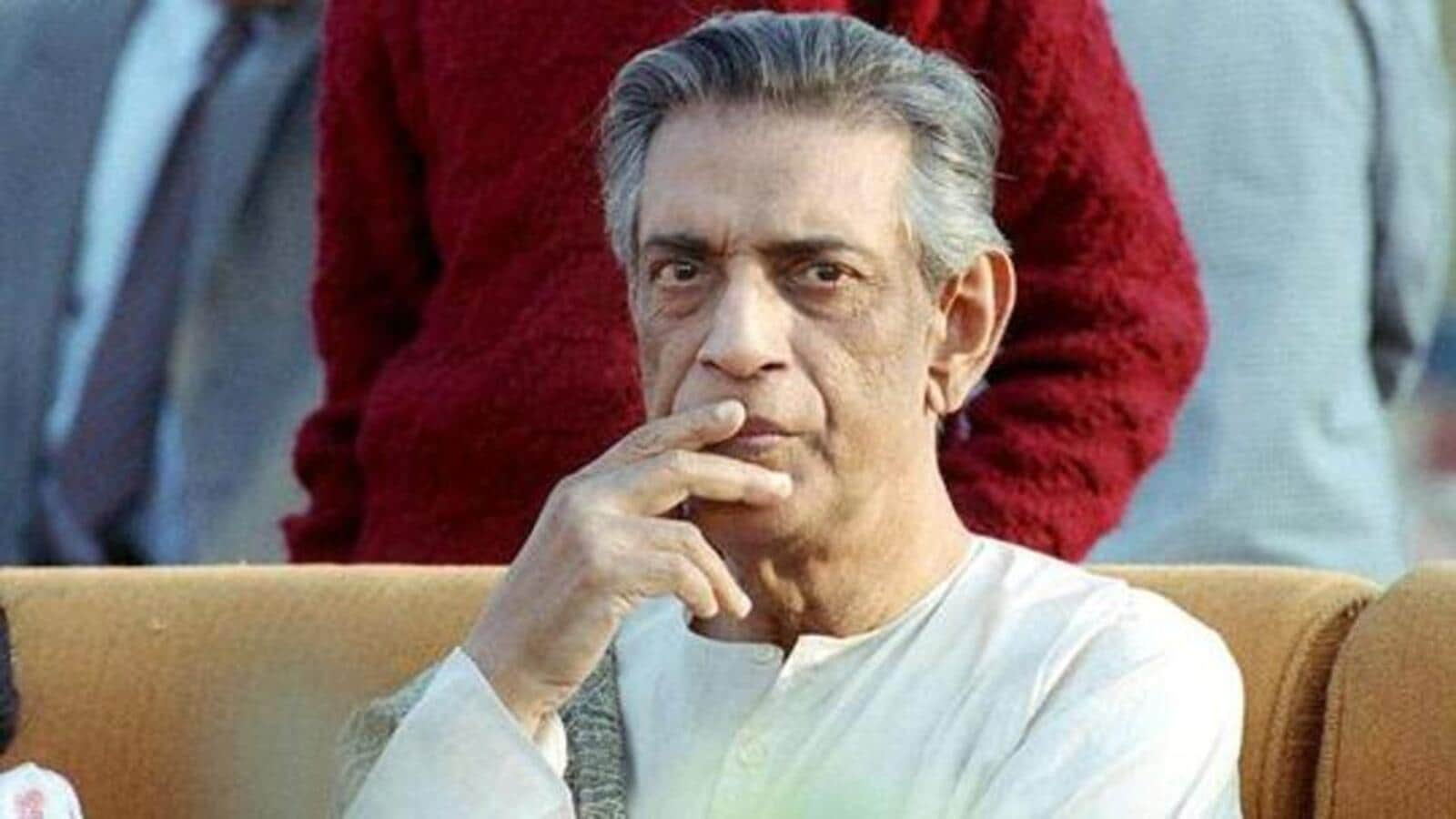

Opinion | Satyajit Ray Through Hindu Lens: The Brahmo Who Never Gave Up Brahman

2025-05-03 01:30:27

On May 3, 1955, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, at its Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India exhibition, screened a film titled The Story of Apu and Durga, later to be titled Pather Panchali or Song of the Little Road. It was well received, although it ran without subtitles.

This May 3, Satyajit Ray’s cinema turns 70. The maestro, incidentally, would have turned 104 on May 2.

If he were alive and still making movies, the most pressing question he would have faced could very likely be about his faith and spirituality. We live in a time of resurgent, assertive Hindutva and a highly reactive Islam. It is a time, ironically, like many of his movies, of black and white.

The maestro would be pressed to take a side.

It is not that he did not face that question during his lifetime. There had been a shrill crescendo of protests after his Devi (The Goddess) released in 1960. The movie is about a young woman who is tragically and almost forcibly elevated to divinity after her father-in-law dreams about her being the incarnation of the goddess.

Hindu conservatives were also furious when Ray’s Ganashatru (Enemy of the People) portrayed how the holy water or “charanamrita” got contaminated because of official corruption and apathy, endangering thousands of lives.

The narrative that Ray was unfairly critical of Hinduness got traction because of his Brahmo faith, a reformist and so-called “progressive” tributary of Sanatan Dharma, pioneered by Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

Later analysis of Ray got even twisted after actor Nargis Dutt, on being nominated to the Rajya Sabha in 1980, in her maiden speech, termed Satyajit Ray as a “peddler of India’s poverty”, an accusation that only someone unfamiliar with his work can make. The hordes who had never watched even a single Ray movie jumped in, painting him as a communist maker of poverty porn.

Ray, ironically, was one of the harshest critics of Bengal’s communist regime, and never hesitated to speak the blunt truth even to the towering CPM patriarch and then chief minister, Jyoti Basu. His Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and Hirak Rajar Deshe are trenchant critiques of totalitarian regimes.

If one looks holistically at Satyajit Ray’s entire body of work, a different picture emerges.

By his own admission, he was against religious dogma and superstition. He was also questioning about organised religion, as we find him articulate in his last movie, Agantuk.

But he was not against religion, spirituality, and mysticism.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Persistence Of Cinema (@persistence.of.cinema)

In fact, the social setting of almost all Ray movies is noticeably Hindu. Except for Shatranj Ke Khilari, there is not even one major Muslim character in his films, even in those set in pre-Partition, Muslim-dominant Bengal.

He made an entire, dazzlingly successful detective movie, Sonar Kella, based on his own Feluda series on reincarnation and rebirth. His fascination and curiosity with “jatishwar”, or those who claim to remember their previous birth, finds its way even in films like Nayak.

He portrays the impoverished village priest Harihar in the Apu trilogy with no malice but almost a tragic-nostalgic fondness. Portrayal of Apu’s childhood has evoked comparisons with little Krishna’s carefree, playful ways.

Ray shunned the long, sermon-filled Brahmo services. His cinematic depiction of the good-intentioned but boring husband in Charulata, although made after Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Nashto Neer, captures the character’s lack of emotional and sexual vitality.

The roots of Ray’s spiritual vision lie in his childhood.

In his essay Through Agnostic Eyes: Representations of Hinduism in the Cinema of Satyajit Ray, Chandok Sengoopta of Birkbeck College, London, writes:

But first, we need to outline just what kind of Brahmo upbringing Ray had and how he reacted to it. Ray’s father Sukumar Ray (1887–1923), who has long been iconic in Bengali literary history for his nonsense verse and other works for children, also distinguished himself as a printing technologist, a photographer, a publisher and magazine editor. Although a committed Brahmo, he and his young associates nearly brought about a split in the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj with their demands for sweeping reforms in structure, administration and ethical code. For Sukumar Ray, the Brahmo movement, despite commencing within orthodox Hinduism as a reform initiative, had diverged so greatly from the parent since then that it had become a sovereign faith, and he did not shy away from a public (and sharply polemical) debate with his close friend Rabindranath Tagore, who, belonging to the conservative Adi Brahmo Samaj, held that Brahmos, in spite of their rejection of many orthodox beliefs and practices, were still members of the larger Hindu family. Sukumar Ray, of course, died at an early age and Satyajit was brought up by his mother Suprabha, whose understanding of the Brahmo-Hindu relationship was interestingly different from her late husband’s. Diligent as she was in attending Brahmo services and shunning festivals such as the “idolatrous” Durga Puja, she wore the iron bangle and vermilion like all Hindu married women. Apart from giving them up after losing her husband, she never dressed again in anything other than the orthodox Hindu widow’s plain white sari (than), despite being reminded by no less a Brahmo luminary than Dr Kadambini Ganguli that her own father-in-law Upendrakishore Ray had decried this custom.

It is perhaps this confluence of childhood strains that makes Ray grey. While he captures the riverbanks and temples of Banaras mesmerisingly in Aparajito (1956) and Joi Baba Felunath (1979), in his Abhijan (1962), a Christian convert feels uncomfortable serving food to the upper-caste hero because she had belonged to an “untouchable” caste before her conversion.

But the clincher that he never snapped away from his Sanatan roots is there in his last movie, Agantuk.

Unlike an Alfred Hitchcock, Quentin Tarantino, or Manoj Night Shyamalan, Ray was not a director who did cameos in his own films. But in Agantuk, a film he shot in his final days, he made an exception.

He sang the iconic ode to Shri Krishna in his own quivering yet baritone voice: “Hari Haray namah Krishna Yadavay namah…”

A final clue to his spiritual self before moving on from the mortal.

Abhijit Majumder is a senior journalist. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

On May 3, 1955, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, at its Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India exhibition, screened a film titled The Story of Apu and Durga, later to be titled Pather Panchali or Song of the Little Road. It was well received, although it ran without subtitles.

This May 3, Satyajit Ray’s cinema turns 70. The maestro, incidentally, would have turned 104 on May 2.

If he were alive and still making movies, the most pressing question he would have faced could very likely be about his faith and spirituality. We live in a time of resurgent, assertive Hindutva and a highly reactive Islam. It is a time, ironically, like many of his movies, of black and white.

The maestro would be pressed to take a side.

It is not that he did not face that question during his lifetime. There had been a shrill crescendo of protests after his Devi (The Goddess) released in 1960. The movie is about a young woman who is tragically and almost forcibly elevated to divinity after her father-in-law dreams about her being the incarnation of the goddess.

Hindu conservatives were also furious when Ray’s Ganashatru (Enemy of the People) portrayed how the holy water or “charanamrita” got contaminated because of official corruption and apathy, endangering thousands of lives.

The narrative that Ray was unfairly critical of Hinduness got traction because of his Brahmo faith, a reformist and so-called “progressive” tributary of Sanatan Dharma, pioneered by Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

Later analysis of Ray got even twisted after actor Nargis Dutt, on being nominated to the Rajya Sabha in 1980, in her maiden speech, termed Satyajit Ray as a “peddler of India’s poverty”, an accusation that only someone unfamiliar with his work can make. The hordes who had never watched even a single Ray movie jumped in, painting him as a communist maker of poverty porn.

Ray, ironically, was one of the harshest critics of Bengal’s communist regime, and never hesitated to speak the blunt truth even to the towering CPM patriarch and then chief minister, Jyoti Basu. His Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and Hirak Rajar Deshe are trenchant critiques of totalitarian regimes.

If one looks holistically at Satyajit Ray’s entire body of work, a different picture emerges.

By his own admission, he was against religious dogma and superstition. He was also questioning about organised religion, as we find him articulate in his last movie, Agantuk.

But he was not against religion, spirituality, and mysticism.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Persistence Of Cinema (@persistence.of.cinema)

In fact, the social setting of almost all Ray movies is noticeably Hindu. Except for Shatranj Ke Khilari, there is not even one major Muslim character in his films, even in those set in pre-Partition, Muslim-dominant Bengal.

He made an entire, dazzlingly successful detective movie, Sonar Kella, based on his own Feluda series on reincarnation and rebirth. His fascination and curiosity with “jatishwar”, or those who claim to remember their previous birth, finds its way even in films like Nayak.

He portrays the impoverished village priest Harihar in the Apu trilogy with no malice but almost a tragic-nostalgic fondness. Portrayal of Apu’s childhood has evoked comparisons with little Krishna’s carefree, playful ways.

Ray shunned the long, sermon-filled Brahmo services. His cinematic depiction of the good-intentioned but boring husband in Charulata, although made after Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Nashto Neer, captures the character’s lack of emotional and sexual vitality.

The roots of Ray’s spiritual vision lie in his childhood.

In his essay Through Agnostic Eyes: Representations of Hinduism in the Cinema of Satyajit Ray, Chandok Sengoopta of Birkbeck College, London, writes:

But first, we need to outline just what kind of Brahmo upbringing Ray had and how he reacted to it. Ray’s father Sukumar Ray (1887–1923), who has long been iconic in Bengali literary history for his nonsense verse and other works for children, also distinguished himself as a printing technologist, a photographer, a publisher and magazine editor. Although a committed Brahmo, he and his young associates nearly brought about a split in the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj with their demands for sweeping reforms in structure, administration and ethical code. For Sukumar Ray, the Brahmo movement, despite commencing within orthodox Hinduism as a reform initiative, had diverged so greatly from the parent since then that it had become a sovereign faith, and he did not shy away from a public (and sharply polemical) debate with his close friend Rabindranath Tagore, who, belonging to the conservative Adi Brahmo Samaj, held that Brahmos, in spite of their rejection of many orthodox beliefs and practices, were still members of the larger Hindu family. Sukumar Ray, of course, died at an early age and Satyajit was brought up by his mother Suprabha, whose understanding of the Brahmo-Hindu relationship was interestingly different from her late husband’s. Diligent as she was in attending Brahmo services and shunning festivals such as the “idolatrous” Durga Puja, she wore the iron bangle and vermilion like all Hindu married women. Apart from giving them up after losing her husband, she never dressed again in anything other than the orthodox Hindu widow’s plain white sari (than), despite being reminded by no less a Brahmo luminary than Dr Kadambini Ganguli that her own father-in-law Upendrakishore Ray had decried this custom.

It is perhaps this confluence of childhood strains that makes Ray grey. While he captures the riverbanks and temples of Banaras mesmerisingly in Aparajito (1956) and Joi Baba Felunath (1979), in his Abhijan (1962), a Christian convert feels uncomfortable serving food to the upper-caste hero because she had belonged to an “untouchable” caste before her conversion.

But the clincher that he never snapped away from his Sanatan roots is there in his last movie, Agantuk.

Unlike an Alfred Hitchcock, Quentin Tarantino, or Manoj Night Shyamalan, Ray was not a director who did cameos in his own films. But in Agantuk, a film he shot in his final days, he made an exception.

He sang the iconic ode to Shri Krishna in his own quivering yet baritone voice: “Hari Haray namah Krishna Yadavay namah…”

A final clue to his spiritual self before moving on from the mortal.

Abhijit Majumder is a senior journalist. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Maria Kostova

Maria Kostova